Make more digital twins

Virtual models boost smart manufacturing by simulating decisions and optimization, from design to operations, explain Fei Tao and Qinglin Qi.

Digital twins — precise, virtual copies of machines or systems — are revolutionizing industry. Driven by data collected from sensors in real time, these sophisticated computer models mirror almost every facet of a product, process or service. Many major companies already use digital twins to spot problems and increase efficiency1. Half of all corporations might be using them by 2021, one analyst predicts2.

For instance, NASA uses digital copies to monitor the status of its spacecraft. Energy companies General Electric (GE) and Chevron use them to track the operations of wind turbines. Singapore is developing a digital copy of the entire city to monitor and improve utilities. Machine intelligence and cloud computing will boost such models’ power.

There is much to be done to realize the potential of digital twins. Each model is built from scratch: there are no common methods, standards or norms. It can be difficult to aggregate data from thousands of sensors that track vibration, temperature, force, speed and power, for example. And data can be spread among many owners and be held in various formats. For example, the designers of a particular car might hold information on its materials and structure, while the manufacturers keep data on how the vehicle is produced and garages retain information on sales and maintenance.

The result? Confusion. A digital twin can fail to echo what is going on in the real world and lead managers to make poor decisions.

Here we set out the main problems and call for closer collaboration between industry and academia to solve them.

Data difficulties

The first step is to decide what types of data to collect3. It is not always obvious. To model a wind turbine, for example, might require monitoring of vibrations from the gearbox, generator, blades, shafts and tower, as well as of voltages from the control system. Torques and rotation rates, temperatures of components and the state of the lubricating oil must also be tracked, together with environmental conditions (wind speed, wind direction, temperature, humidity and pressure).

Missing or erroneous data can distort results and obscure faults. The wobbling of a wind turbine, say, would be missed if vibration sensors fail. Beijing-based power company BKC Technology struggled to work out that an oil leak was causing a steam turbine to overheat. It turned out that lubricant levels were missing from its digital twin.

The optimal number and placing of sensors must be determined. Too few, and predictions will be inaccurate; too many, and the user will be mired in detail. The rate of data collection also matters. Engineers might monitor vibrations from a turbine gearbox every minute, meaning they would miss shorter glitches. But sampling every second could yield way too much data, leading to transmission bottlenecks.

To illustrate: Google’s self-driving car could produce 1 gigabyte of data each second, according to some estimates. But today’s bluetooth connections can handle only 0.03% of that rate.

Disparate data types are hard to merge, too. Vibrations can be recorded as lengths of time or as frequencies; temperatures can be in celsius or fahrenheit; and videos or images might not be to the same scale. Timings can get out of step, especially when data are sampled at different rates. For example, aircraft communication systems send signals every few nanoseconds, while navigation systems record the position of a plane every second. Averaging fine data doesn’t help because detail is lost.

Scattered ownership of data is another barrier. For instance, Boeing aircraft include parts from more than 500 suppliers in 70 countries, each with different data interfaces, formats and software. Companies often don’t want to share commercially sensitive information. Nor do countries: Japan restricts the export of some computer chips to competitors in South Korea, and the United States bans the sale of chips and other technology to Chinese company Huawei.

Model challenges

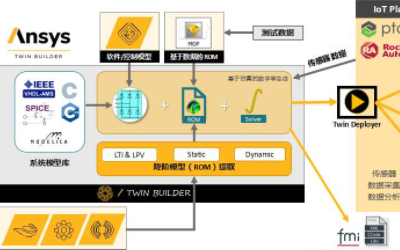

To build a digital twin of an object or system, researchers must model its parts. The German manufacturing company Siemens uses many mathematical models and virtual representations of its products and production lines. These include 3D geometric models and finite-element analysis, the latter for tracking temperatures, stresses and strains. Fault diagnosis and life cycles are treated separately.

Other errors could arise when software written for different purposes is patched together by hand. And without standards and guidelines, it is hard to verify the accuracy of the resulting models. Many digital twins might need to be combined. For example, a virtual aircraft might incorporate a 3D model of the fuselage with one of a fault-diagnosis system and one monitoring the air conditioning and pressurization.

Even the definition of a digital twin is not settled. Some people think any 3D model or simulation counts. More ambitiously, others envisage a set of integrated models or software that pairs the digital world with physical assets, with or without live information from sensors. Each approach has its own norms, with little crossover.

Twin teams

A close-knit team of specialists spanning disciplines is thus essential to building a precise digital twin. No one person can know every detail. Materials scientists, metallurgists and mechanics might need to work with engineers, computer scientists and manufacturing experts. The range of disciplines needed will widen as applications diversify.

Most digital twins are found in large companies such as GE or Siemens, because it is difficult and expensive to assemble the teams required. With commercial pressures dissuading businesses from sharing models, smaller firms lose out.

There is a lack of common space — physical and virtual — in which experts can communicate and share knowledge and software. And there are few connections between industry and academia, in part because of commercial secrecy. Most academic research focuses on improving modelling techniques rather than on optimizing data and implementing digital twins.

Four bridges

The following steps would make research and development of digital twins more coherent.

Unify data and model standards. Manufacturing data should be standardized and delivered in common formats such as XML (Extensible Markup Language), which is used in areas from electronic commerce to supply-chain software. Other data standards should be adopted where they exist. For example, the electricity sector uses COMTRADE (‘common format for transient data exchange’), a standard overseen by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers; the construction industry uses Industry Foundation Classes; and international health-care organizations require data to conform to HL7 (Health Level 7) standards.

A universal design and development platform for digital twins should also be developed on which all models can run. One step in the right direction is a virtual shared workspace, the Global Collaborative Environment, created by aircraft maker Boeing to align practices among its corporate partners. Corporations, foundations, universities and governments should set up and fund an association to oversee a broader one. It could emulate the chip industry’s non-profit research consortium founded in 1982. Called the Semiconductor Research Corporation, this is based in Durham, North Carolina.

Share data and models. A public database for sharing digital twins should be created, to be managed by government funding agencies or by a coalition of universities and enterprises. Issues of data ownership and openness will need to be addressed.

One such example is the openVertebrate platform, funded by the US National Science Foundation. It allows researchers to freely share data and models of vertebrate anatomies. Digital images and 3D mesh files can be explored, downloaded and 3D-printed on MorphoSource, an open-access online database. Curators can oversee ‘virtual loans’ of their specimen data and receive updates on their use.

Platforms of this kind would allow researchers from industry to purchase digital twin data and models, or to lease them to others to conduct research and develop business applications.

Innovate on services. Companies should develop products and services to help digital twins become easier to build and use. For example, Siemens’ NX software combines design, simulation and manufacturing tools in one package. Canadian company LlamaZOO has developed a virtual-reality/augmented-reality application that enables mining supervisors to monitor their vehicles. The virtual forest developed by Metsä Group, Tieto and CTRL Reality, all based in Finland, simulates different forest-management methods and their impacts on income and the landscape.

Establish forums. Practitioners and researchers need an online space where they can discuss, develop and publish specifications. That is why, in 2017, we set up a social media group on digital twins on the Chinese social-media platform WeChat. Foundations, universities and companies should offer similar forums.

Physical ‘innovation hubs’ should also be set up in mutually accessible locations to connect industry, data scientists, cybersecurity experts and engineering and business strategists. One example is the Smart Innovation Hub on the campus of Keele University, UK, alongside Keele Business School. And business consultants Booz Allen Hamilton run several such hubs in Washington DC, near federal government agencies.

Nature 573, 490-491 (2019)

doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-02849-1

References

1. Tao, F., Zhang, M. & Nee, A. Y. C. Digital Twin Driven Smart Manufacturing (Academic Press, 2019).

2. Pettey, C. ‘Prepare for the impact of digital twins’ (2017). Gartner report available at https://go.nature.com/2krzbjd

3. Kusiak, A. Nature 544, 23–25 (2017).